How do Lean Techniques Improve Quality?

The two most popular process improvement initiatives in businesses today are Lean and Six Sigma. Both methodologies are rooted in American manufacturing productivity techniques developed and enhanced from the early 1900’s through World War II. These techniques proved to be successful, as the American military was able to mass produce weapons and aircraft, helping lead the Allied Forces to victory.

However, after World War II, the Japanese took a different approach when learning these techniques to help rebuild their economy with limited natural resources. They adopted a different mindset and management system to be able to compete. The success of Toyota and their Toyota Production System became one of the most studied programs to better understand what the Japanese had developed. This led to the term “Lean,” because of fewer resources, faster production times, smaller inventory and fewer defects observed by research teams.

Six Sigma was also based on the techniques of early American productivity, but focused more heavily on the statistical methods. Motorola developed Six Sigma to help improve their quality performance, as they were losing market share to Japanese competitors in the late 1970’s. It also proved successful, saving millions of dollars for companies like Allied Signal, Honeywell and General Electric.

Like this history? Read more about where Lean and Six Sigma came from

Since early 2000’s, Lean Six Sigma has become the popular term, which is meant to be a combined hybrid approach of the two methods.

One of the reasons these methods were combined was likely because of the perception that Six Sigma is only used for solving quality problems, and Lean is only used for making the process go faster. To satisfy customers, you obviously need to give them what they want (high quality using Six Sigma), and give them the product or service quickly (speed using Lean), thus Lean Six Sigma is the answer!

In fact, that was my perception when I first started to learn about Lean methods in 1999 (coming from a Six Sigma background). It took me a few years to realize that was a false statement (thank you Mark Graban).

Lean methods actually have a very strong focus on quality. It makes a lot of sense. It takes longer to fix a problem and do a process more than one time, and that’s not good for customer speed or quality.

Here is what I learned over the past 20 years that changed my perception about quality improvements within Lean.

1) Defects are waste

One of the 7 forms of wastes that Taiichi Ohno (credited with developing the Toyota Production System) described was defects (originally called “muda of repair/rejects”). When you have a defect in your process, you waste time inspecting to find it (it probably has occurred before). You also waste time recording information about the defect, troubleshooting the problem, repairing or fixing the defect (or starting over at even higher cost), then re-inspecting the repair to make sure it’s good. Repaired and reworked items are often less reliable and more prone to latent issues, which impacts customer satisfaction.

To summarize, defects slow down the process, add more time and labor to the process, and provide an inferior product or service to the customer. Therefore, doing the work right the first time is the most efficient way to do work.

2) Standard work

One of the key methods of Lean is to establish a standard approach for doing the work. This is not just a procedure or work instruction on how an engineer or process owner thinks the work should be done. Rather, it’s a collaborative activity to work with the actual workers to define the best approach to do the work that everyone can follow. What this results in is a user-friendly document or reference that is placed in the work area, readily accessible to the worker, to help them do the job correctly every time. This posted document should highlight key steps or elements that are often missed or confusing. This should supplement and support the training they have already received. A 3-ring binder with a very wordy document that is never used by the worker is not acceptable.

In order to fix problems, there must first be a common way of doing the work. If the standard does not exist, start by getting the workers together to capture best practices and teach everyone how to do the work the same way. The focus should be on the aspects of the process that actually impact the quality of the product or service, so you shouldn’t try to standardize every little thing. This standardization work can quickly reduce many errors and mistakes.

When there is another similar problem that occurs, we can now more easily determine what happened, because everyone is doing the process the same way. If the worker followed the standard work, then perhaps the process needs to be changed. If they didn’t follow the process, then we need to understand the root cause for why it wasn’t followed (which might be a legitimate reason).

“Where there is no standard, there can be no kaizen (improvement)”

Taiichi Ohno

3) Error proofing (poka-yoke)

Shigeo Shingo was a consultant who worked at Toyota, working closely with Taiichi Ohno and helped develop the Toyota Production System (the basis for Lean methods). From a quality standpoint, he is most responsible for the concepts of error (mistake) proofing, which was called poka-yoke in Japanese.

Poka-yoke is under the broader topic of Zero Quality Control (ZQC). He wrote numerous books about his work and experiences, and taught Industrial Engineering courses in Japan, including his most famous P-course (P stands for Production).

He wrote two books on this topic:

- “Zero Quality Control: Source Inspection and the Poka-yoke System”

- “Mistake-Proofing for Operators: The ZQC System“

These books share the best practices of techniques he developed to reduce the chance of errors and defects in the process. He knew that human errors were inevitable, so instead of telling workers to “try harder” or “be more careful,” he developed effective and low-cost ways to prevent or quickly detect problems.

One of his early examples was in a switch assembly process. One frequent defect was a spring that was often left out of the assembly. He helped redesign the process to break up the work into two processes, one step to prepare the springs into a placeholder, the other to assemble into the switch assembly. If a spring remained in the placeholder, then the workers knew that something is wrong.

Another example is pre-counting the correct number of screws for an assembly into a petri dish. The worker would pull the pre-counted screws directly from the dish, instead of a large bulk bins of screws. If they have an extra screw in the dish, then it highlights a potential problem (miscounting of screws, or worker didn’t install all of them). The problem is caught and corrected right away, instead of much later in the process (perhaps all the way to the customer).

Again, these are both low-cost and effective methods to improve quality.

4) Problem solving structure and coaching

Lean focuses on engaging workers in the problem solving process through quality circles. Leaders and supervisors are responsible for coaching their employees on how to solve problems, not solving the problems for them. The 8-step problem solving process is a standard method used at Toyota to help facilitate this learning.

The original model came from Dr. W. Edwards Deming, an influential American consultant who worked on quality improvements during World War II, then went to Japan to help them rebuild after World War II. He called the model Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA), derived from the original Plan-Do-Check-Act model from Walter Shewhart, one of Deming’s mentors. It was a simple model for thinking through the scientific process. Years later, Toyota evolved to the 8-step Problem Solving model, which provides more details and guidance about each of the steps. The American automotive industry also adopted an 8-step model, called 8D (8 disciplines).

Regardless of the model used, the goal is to help teach the worker how to better solve a problem. Their manager or supervisor checks their progress against the model on a frequent basis, so no steps are skipped and no incorrect assumptions are made. Often times, a single sheet of paper is used to communicate their progress during these reviews (called an A3, named after the size of paper).

Six Sigma also uses a problem solving model, called DMAIC:

- Define

- Measure

- Analyze

- Improve

- Control

This is very similar to the 8-step and PDCA models.

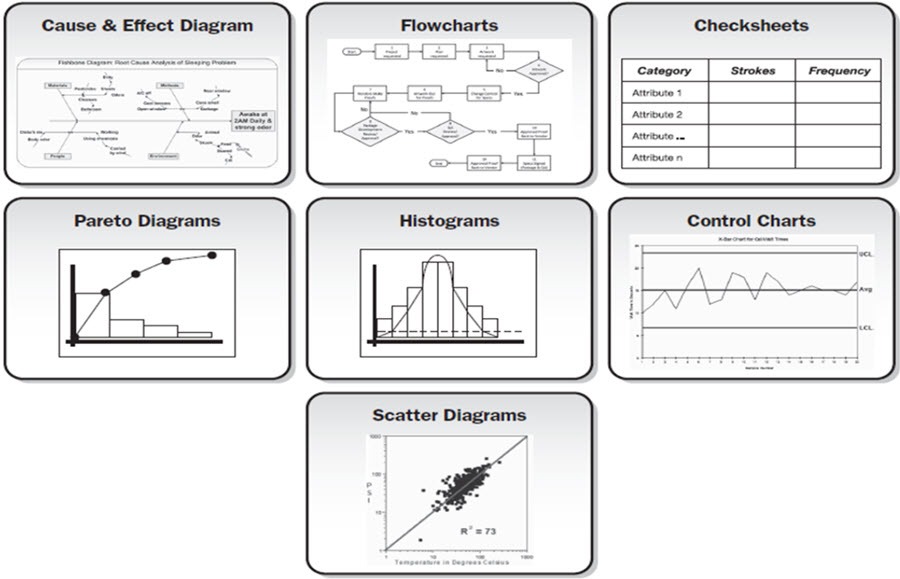

Within these problem solving models, both Lean and Six Sigma promote the use of the most common problem solving tools, called the 7 Quality Tools.

These tools are fundamental within quality circles and Total Quality Management (TQM), and carried over into Lean and Six Sigma methods.

Bottom line, companies that establish a standard method for solving problems are more effective for making improvements. It provides a common language for teams on where they are in the process, and helps the leaders and supervisors better coach and mentor their teams. Following a common process also prevents teams from jumping ahead to solutions, and increases their chance of actually solving the problem (where defects and errors are often a focus for these improvements).

If Lean addresses quality issues, why do we need Six Sigma?

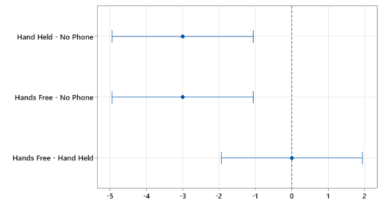

When the quality problems become more challenging and difficult, I’ve found that the use of more statistical methods can be really beneficial. This is especially true after I’ve attempted team-based problem solving, implemented standard work and increased the use of error proofing devices.

To summarize, I’m a big fan of both Lean and Six Sigma methods. They work well together to solve most problems within an organization. Going forward, when looking to improve quality in your process, don’t forget that the tools and methods within Lean are very effective at engaging your teams in this effort. Not every problem requires advanced statistical methods to solve.

Lean teaches us to work closely with the workers in their work area to understand their challenges, and look for ways to coach them through the problem solving process. Look for opportunities to apply standard work and error proofing first, before jumping to the more advanced techniques of Six Sigma, such as designed experiments and regression analysis.